The riotous profusion of conspiracy theories in America shows us something about being American, even about being human—about the decisions we make in interpreting the complexities of our surroundings. Over and over, I found that the people involved in conspiracy communities weren’t necessarily some mysterious “other.” We’re all prone to believing half-truths, forming connections where there are none to be found, finding importance in political and social events that may not have much significance at all. That’s part of how human beings work, how we make meaning, particularly in the United States today, now, at the start of a strange and unlikely century.

Anna Merlan, Republic of Lies (pp. 8-9)

Don’t neglect me

Come be my conspiracy

The Black Crowes, “A Conspiracy”

As a #repentingexconspiracytheorist I feel a lot of feelings watching folks fall into the deep dark well of conspiracy. I feel a tremendous amount of sadness, especially when people in my own spiritual community appear to have more devotion to QAnon than they do to the actual Divine. It’s a sadness born from some experience, from an experiential knowledge that the lure of the conspiracy is like the tragic lure of Dionysus in The Bacchae. What seems intoxicating becomes poisonous. I feel no small amount of anger at the devotees of conspiracy theory. Often I feel like Buzz Aldrin, wanting to send my fists flying at the nearest something-or-other denying dweeb. I feel a whole awful lot of bewilderment and vertigo and la nausee that conspiracism now feeds on the global body politic like a ravenous, metastasizing, mutative virus.

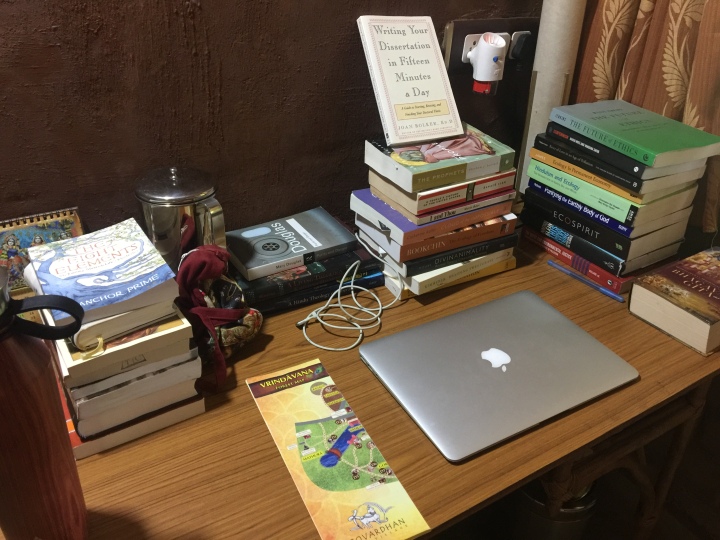

In the last year there has been a tremendous amount of critical journalism and scholarship about the conspiracizing of our commons. I can’t recommend enough Republic of Lies: American Conspiracy Theorists and Their Surprising Rise to Power by Anna Merlan, Conspiracies of Conspiracies: How Delusions Have Overrun America by Thomas Milan Konda, and of course the OG classic of the field “The Paranoid Style in American Politics“, the November 1964 essay from Richard Hofstadter. Along with such great recent essays such as “Conspiracy Theories Can’t Be Stopped” by Maggie Koerth-Baker and “QAnon and the Emergence of the Unreal” by Ethan Zuckerman.

These books and essays offer a careful, considerate, and by all means critical survey/deep dive into the realm of conspiracy theories and the ideology of conspiracism from which these theories gestate. What is conspiracism? From Republic of Lies we learn:

The historian Frank P. Mintz coined the term “conspiracism,” which he defined as a “belief in the primacy of conspiracies in the unfolding of history.” Conspiracism works for everyone, in Mintz’s view; it “serves the needs of diverse political and social groups in America and elsewhere. It identifies elites, blames them for economic and social catastrophes, and assumes that things will be better once popular action can remove them from positions of power.” It is, in essence, a view of how we can vanquish the Devil and achieve Heaven right here on earth. (1)

Ay here’s the rub for what I hope I can contribute to this vibrant and urgent conversation: conspiracy theories and conspiracism are a reality (or unreality) which emerges from deep spiritual alienation and which requires a compassionate but very firm and tough spiritual response. We need tough-love theology here.

In my previous essay in this series I wrote:

To be a conspiracy theorist is to participate in something which resembles a spiritually rooted existence, a human life striving for Divine connection and communion. As I have come to learn from my own experience, to be a conspiracy theorist is actually a very distinct and destructive perversion of a genuine spiritual life. There is a thin line between genuine, sincere curiosity at discovering the hidden matrix of our collective living experience and becoming a damaged soul whose paranoia becomes a stone obstacle to love and liberty.

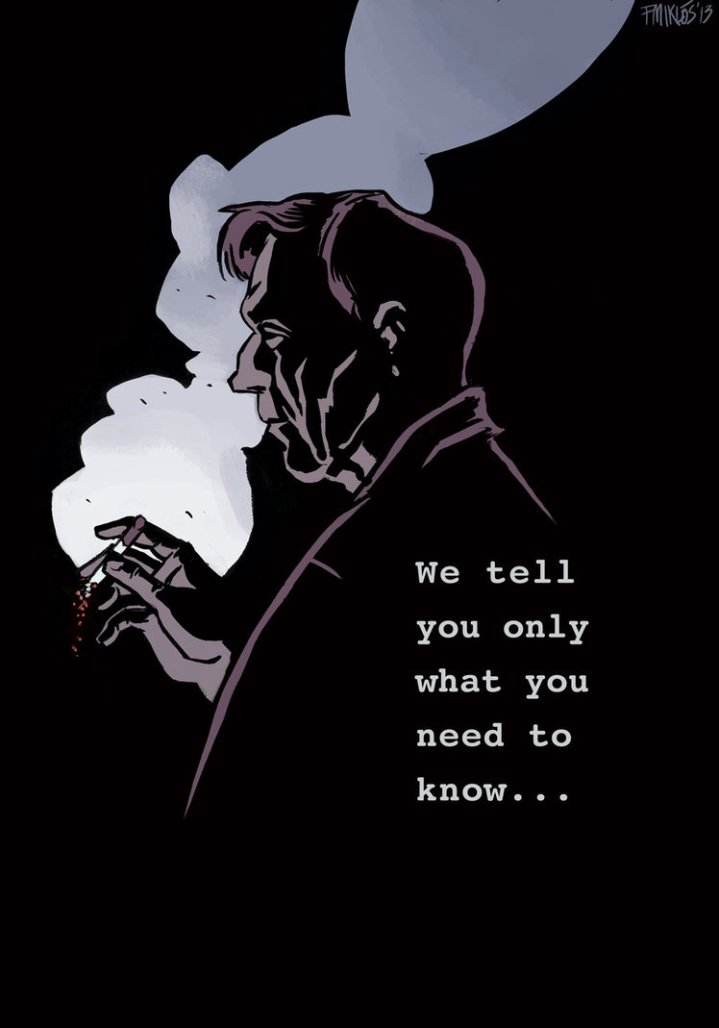

I thank the Lord I never fell into the deepest dank hells of the conspiracy mindset, but I can say I stood over the abyss and saw clearly enough there was a circle yet to be discovered by Dante. The Hell of the Conspiracy Theorists: forever chained to their computers, palest than the palest specter, continuously attacked by Cuban mobsters, Elders of Zion, reptilian aliens, and the Cigarette Smoking Man.

There is that mantra some of us always chant when we see the roads not taken: There but for the grace of God go I. When I see members of my spiritual community having driven themselves so deeply down this dark road, I have to temper the waves of disgust which are my first reaction and strive for a different feeling. I mean all glories to Buzz Aldrin’s righteous fists of fury, but that’s only one of many constructive responses to those who have swallowed various varieties of the red pill. I want people who’ve taken this pill to vomit it up, but I also hope I can be the kind of person who can help nurse them back to health.

While I never fell so far down the rabbit hole that I began to openly flirt with the misogynistic, racist, fascist, and anti-Semitic poison of the conspiracist swamp, I understand, deeply, intimately, and from experience, how enchanting and liberating it seems to be to have entrance to the inner sanctum where nothing is true and everything is permitted. When the burdens of our chaotic, precarious reality become more than we are capable of handling, Unreality becomes exquisitely attractive. Unreality is the result when the natural reality of our differing experiences of reality becomes a war zone. As Ethan Zuckerman describes in his excellent essay on QAnon:

I have started to think of this clash of realities as “the Unreal.” I don’t mean to identify a singular unreality—Trump’s, QAnon’s, or anyone else’s—but to make the point that what’s real to you is unreal to someone else. Like conspiracy theories, this is not a new phenomenon. Questions of whether we can share a common reality or whether we will be forever separated by our perceptions and interpretations are the subject of timeless debates in epistemology and phenomenology. What’s different now is that these debates have escaped the philosophy classroom and are now infecting every news story and online discussion.

We can’t just demonize ourselves or others for our attraction to the Unreal, but we can’t sit back and accept that our every breath (hello climate change deniers-the ones I most want to punch) and our every thought and our every utterance and our every need for relationship is increasingly threatened by the infection of the conspiracy. Whether you have stepped back from the void as I am always trying to do, or whether you’re just super-rational and have never been tempted by such dark arts, or whether this is a topic which has never piqued your interest, we share a common responsibility to respond to the onslaught of the Unreal with courage, compassion, and a desire to heal the existential and spiritual wounds from which conspiracism emerges.

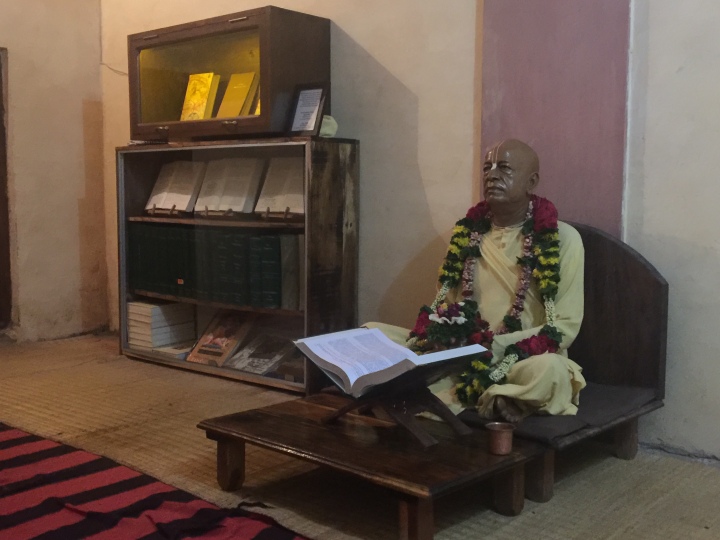

The Hindu/Vaishnava tradition which I practice in and identify with posits and teaches that we, as living, thinking, willing, and feeling beings, are particularly drawn to and attracted by maya (illusion). Our sense of self-identity, our ego-self, when covered over by such illusion, interprets reality through the lens of the ahankara (the alienated ego). The ahankara is the perception of our self-identity which leads us away from our actual self-identity. The ahankara is the lens through which we experience reality as Unreality.

As beings full of desires for happiness and well-being and intimacy and tactile pleasure, when our desires are turned away from what is healthy for us, from what helps us flourish, towards what inflames our selfishness and our alienation from others, then we are stuck and lost in our ahankara. In the Bhagavad-Gita, Krishna describes what happens when our desires for happiness are broken and turned inwards on ourselves in a destructive way:

For a person dwelling on the objects of the senses, attachment to them develops; from attachment, selfish desire develops; from desire, anger develops.

From anger comes bewilderment; from bewilderment, disturbed memory; from disturbed memory, loss of discernment; from loss of discernment one becomes lost. (Chapter 2: Verses 62-63) (2)

My brothers and sisters lost in the void of the conspiracy deserve, at the least, a broad and compassionate understanding of where there desires have led them astray. Desires for truth, clarity, and understanding are not wrong. They are innately part of our everyday being at all times. As beings we are always seeking sat-cit-ananda (eternality, understanding, and happiness). In my previous essay I wrote:

The Vedic/Hindu scriptures teach that every living being is striving for sat-cit-ananda consciousness: for our original state of spiritual being: eternally existing, eternally cognizant, eternally blissful. Every human being is instinctually always striving for this consciousness at every single moment. Every act is either an act of love or a cry for love. Yet we live in a turbo-capitalist alienated culture which very nearly completely corrupts and curdles this instinct. Instead of becoming natural sages and saints in beloved community, we become devotees of conspiracy. Our faith settles in the nefarious, the occult, the total illusion of maya. Our faith settles in untruth and becomes ultimately faithless, inhumane. We become like a riven cloud, in a 4chan message board, a shattered simulacrum of our real self.

I want to try to approach those stuck in the desert of the real as someone who has once walked along that barren road. As someone who learned to walk back towards what is actually nourishing for life, understanding, and happiness. We can parse out the whys and whens and hows of how conspiracy theories and conspiracism emerges and festers and multiplies. All of this work of discernment is immensely important and necessary, but I’m afraid we can’t actually begin to heal the wounds of such a phenomenon unless we understand the existential and spiritual wounding which is the root cause of why conspiracies are so attractive to so many people.

In the next essay in this series, I will share and explore with you further the phenomenon of agnotology, or the cultural production of ignorance, and how Hindu concepts of avidya (ignorance) on an existential and spiritual level help us to understand why the Unreal is so prevalent and so attractive.

- Merlan, Republic of Lies, 14.

- Translation from Graham M. Schweig, Bhagavad Gita: The Beloved Lord’s Secret Love Song.